1

Lesson 2:

Eccentric

Triphasic Training - The Difference

Many traditional training methods teach athletes how to expel energy; little time and effort are spent teaching them to absorb it. That is the entire point of the Triphasic method—learning how to eccentrically and isometrically absorb energy before applying it in explosive dynamic movements. Athletes aren’t powerlifters. They must be strong, but only to the extent that it can benefit them in their sport. Every dynamic human movement has a limited amount of time in which the mover can produce as much force as possible. Ben was a world-class thrower because he could generate more explosive strength (defined as maximal force in minimal time) in the time it took to throw a shot.

Most training methods focus on the development of explosive strength by emphasizing the concentric phase of dynamic movement. My epiphany in 2003 was that we were approaching the development of force from the wrong angle. The key to improved force production, and thus sport performance, doesn't lie in the concentric phase. To develop explosive strength, you must train the eccentric and isometric phases of dynamic movements at a level equal to that of the concentric phase.

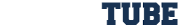

Look at the figure below. Imagine the graph as depicting the same athlete at different times during his or her development. The lines are the same athlete, but one shows the results of an athlete developed using triphasic training and the other in the early stages of development. Your new goal as a strength and conditioning coach or athlete is to narrow that V as much as possible.

Eccentric

An eccentric action can be defined as when the muscle attachments closest and farthest from the center of the body (proximal and distal) move in opposite directions. This is often referred to as the lengthening, or yielding, phase, since the muscle is stretched due to a load placed on it.

Now, read this next part very carefully. Every dynamic movement begins with an eccentric muscle action. For example, when you jump, your hips perform a slight dip, eccentrically lengthening the quads and glutes before takeoff. This countermovement is critical to power production. The eccentric phase sets in motion a series of events that pre-load the muscle, thus storing energy to be used in an explosive, concentric and dynamic movement.

When you train the eccentric phase, two physiological processes contribute to force development. One is the most powerful human reflex in the body—the stretch reflex. The other, whose force producing abilities depend on the stretch reflex, is a close second in terms of force production. It is called the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). (Although it’s important to understand these processes, they are outside the scope of this article. For now, just accept the fact that they’re important.)

Let’s go back to the “V” from Part 1 of this series so you can see exactly what I’m talking about. When you look at the graph below, you begin to see the correlation between the eccentric and concentric phases. The steeper the eccentric line is coming into the bottom of the “V,” the steeper the concentric line is leaving the bottom of the “V.” The greater the velocity of stretching during the eccentric contraction, the greater the storage of elastic energy. The athlete who can handle higher levels of force through an increased stretch reflex will be able to apply more force concentrically and be able to jump higher or use more power in other explosive movements.

To safely maximize eccentric adaptation, I have derived a few rules, which, when followed, yield the best results for athletes performing eccentric training.

1. Due to the intense stress placed on an athlete by eccentric training, its application should be limited to large, compound exercises.

When an athlete is first exposed to eccentric training, his or her physiological system will likely only be able to handle one compound exercise per workout. The exercise should be performed early in the workout while the nervous system is fresh.

2. Never perform slow eccentrics with loads greater than 85 percent of an athlete’s one-rep max.

This rule is based on my own risk versus reward analysis. To me, the risk is far too great to have an athlete use weight close to, at or above his one-rep max for an extended period of time. I’ve seen torn pecs and quads, blown backs and injured shoulders. At the end of the day, you can get the same physiological adaptation using lighter loads for longer times with half the risk.

3. Always use a spotter when performing slow eccentrics.

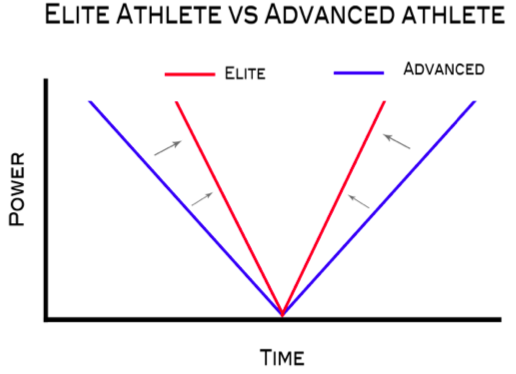

You must remember that when performing eccentric training, the body is being maximally fatigued. As you can see in Table 3.2, as the load decreases, eccentric time increases. The resulting increase in time under tension means an athlete’s muscular system could give out at any point during the lift, so proper spotting is crucial.

4. Always finish an eccentric focused lift with an explosive, concentric movement.

The most important aspect of performance—one that you’re constantly trying to improve—is the nervous system. Every jump, cut and throw begins with an eccentric lengthening of the muscle and ends with an explosive concentric contraction. The bar will not necessarily move fast, especially when you use heavy eccentric loads, but the intent to accelerate the bar, changing over from an eccentric to a concentric signaling pattern, must be firmly emphasized with every rep.

Example Exercises with Eccentric Means and Coaching Points

1. Set up with the bar on the back of the shoulders.

2. Keeping the chest up and the back flat, sit back as if to a chair.

3. Descend into the bottom of the squat in the prescribed time.

4. Once the time has been reached, explosively fire up back to the start.

1. Set up with the bar on the front of the shoulders.

2. Keeping the chest and elbows up and the back flat, sit back as if to a chair.

3. Descend into the bottom of the squat in the prescribed time.

4. Once the time has been reached, explosively fire up back to the start.

1. Grab the bar just outside of the thighs with the feet shoulder width apart.

2. Keeping the back flat and the chest up, bend the knees slightly.

3. Allow the bar to slide down the thighs for the prescribed time.

4. Once the time has been reached, explosively fire up back to the start.

1. While laying on your back, grab the bar one thumb length away from the knurling.

2. Unrack the bar, keep the shoulders pulled back, and pull the bar into the chest.

3. Lower the bar in the prescribed time until it touches the chest.

4. Once the time has been reached, explosively fire up back to the start.

1. Begin standing with a dumbbell in each hand, palms facing each other.

2. Press the dumbbells up explosively to begin the exercise.

3. Lower the dumbbells back to the shoulders in the prescribed time.

4. Once the time has been reached, explosively fire up back to the start.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

Triphasic Baseball Training Manual Transform your baseball performance with our Triphasic Baseball Training Manual. This expertly crafted course offers comprehensive training methods, personalized plans, and cutting-edge techniques designed to enhance speed, agility, and overall athletic capabilities for baseball players. Why Choose Our Training Course? Expert-Led Training: Learn from top coach...