Featured courses

- Two Great Game Situational Workouts For the Basketball Offseason by Grant Young

- Two Reads Basketball Players Must Understand Before Executing the Ball-Screen by Grant Young

- Two of LSU Coach Kim Mulkey’s Game-Winning Inbounds Plays by Grant Young

- Three Effective Early-Season Defensive Basketball Drills by Grant Young

- Four Essential Tips For Basketball’s 1-3-1 Zone Defense by Grant Young

- Four Zone Defense Drills to Strengthen Your Team by Grant Young

- How to Beat the Three Most Common Pick and Roll Coverages by Grant Young

- Two Drills to Improve Shooting at the Start of the Basketball Season by Grant Young

- Core Basketball Principles That Dallas Mavericks Coach Sean Sweeney Teaches by Grant Young

- Three Competitive Shooting Drills For Your Basketball Team by Grant Young

- How To Teach The ‘I’ Generation of Basketball Players by Grant Young

- Three Elite Drills to Begin a Basketball Practice With by Grant Young

- How to Build a Championship-Winning Basketball Team Culture by Grant Young

- Two of Texas Women’s Basketball Coach Vic Schaefer’s Tips For Team Culture by Grant Young

- Atlanta Dream WNBA Coach Brandi Poole’s Four Sets for Secondary Offense by Grant Young

- NC State Basketball Coach Brett Nelson’s 4 Crucial Point Guard Qualities by Grant Young

- Kentucky Coach Mark Pope’s Five Guard Rules For Offense by Grant Young

- McNeese State Basketball Coach Will Wade’s 4 Core Pillars by Grant Young

- 4 Tips To Instantly Improve Your Free Throw Shooting by Tyler Linderman

- Assemble a Championship-Caliber Basketball Rotation by Brandon Ogle

- Two of UConn Coach Dan Hurley’s Key Defensive Drills by Grant Young

- Four Post Moves All Basketball Forwards Should Have In Their Bag by Grant Young

- Four of Baylor Coach Nicki Collen’s Midseason Pick and Roll Adjustments by Grant Young

- WNBA Legend Sue Bird’s Two Tips For Attacking on Offense by Grant Young

- Houston Coach Kelvin Sampson’s Three Keys for Building a Basketball Program by Grant Young

- Two of Tom Izzo’s Top Michigan State Defensive Drills by Grant Young

- Four of Olympic Gold Medalist Coach Mechelle Freeman’s Relay Race Strategies by Grant Young

- Three Key Strategies Will Wade Uses to Build a Dominant Team by William Markey

- Five UConn Huskies Men’s Basketball Plays That You Can Use by Grant Young

- Three Tips for Maintaining Team Culture at the End of a Basketball Season by Grant Young

- Three Dribble Drive Motion Drills to Teach Your Basketball Team by Grant Young

- Three Dribbling Drills For Non-Primary Ball Handlers by Grant Young

- Four Advanced Ball Handling Drills For Basketball Guards by Grant Young

- Three Tips to Sharpen Your Post Player’s Footwork in Basketball by Grant Young

- These Three Pick and Roll Drills Are Crucial For Any Ball Screen Offense by Grant Young

- Three Closeout Drills to Improve Basketball Shooting Defense by Grant Young

- Three Tips to Perfect the Packline Defense in Basketball by Grant Young

- Four Keys to Executing the Read and React Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- Three Tips to Develop Elite Basketball Shooters by Grant Young

- Three Crucial Keys to Executing the 5 Out Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- These Three Offensive Sets Will Help You Beat Any Zone Defense by Grant Young

- Three Transition Basketball Drills To Play With More Pace by Grant Young

- Three 5 Out Offense Drills Any Basketball Coach Can Use by Grant Young

- Four Vital Techniques for a Motion Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- Three Baseline Inbounds Plays To Win Your Basketball Team Games by Grant Young

- Four Drills For Sharpening the European Ball Screen Offense by Grant Young

- Three Positioning Tricks For a Basketball Zone Offense by Grant Young

- Three Rules to Perfecting Basketball's Lock Left Defensive System by Grant Young

- UCLA WBB Coach Cori Close’s Two Keys to Winning the Mental Game by Grant Young

- Four of Alabama Coach Nate Oats’ Favorite Basketball Drills by Grant Young

- Three Ways To Turn Transition Offense in Basketball Into Points by Grant Young

- Three Drills to Master Basketball's Pack Line Defense by Grant Young

- Three Transition Defense Drills to Halt Fast Breaks by Grant Young

- Four Offensive Rebounding Drills to Win Second Possessions by Grant Young

- 4 Defensive Technique Drills from Boston Celtics Assistant Coach Brandon Bailey by Marek Hulva

- 5 Drills to Improve Ball Handling by Tyler Linderman

- 13 FUNNY BASKETBALL GIFS by Alex

- BASKETBALL SPEED AND AGILITY: 8 QUESTIONS FOR COACHTUBE EXPERT RICH STONER by Jaycob Ammerman

- Defensive Strategies for Basketball by Ryan Brennan

- 4 Keys To Turning Your Program Into Championship Contender By Dallas Mavericks Coach Sean Sweeney by Marek Hulva

- 5 Components to Creating a Winning Basketball Program by Justin Tran

- Guide to Becoming a Lethal Scorer in Basketball by Justin Tran

- Zone Defense In the NBA Eastern Conference Finals by James Locke

- Mastering Court Mobility: Tips for Effective Movement in Basketball by Justin Tran

- 5 Basketball Shooting Drills: How to Develop a Sharpshooter by James Locke

- 6 Points of Emphasis for a Successful 5 Out Offense by Jaycob Ammerman

- Effective and Efficient Methods to Practice During the Basketball Season by Justin Tran

- Three Great Passing Drills From a Basketball Coaching Legend by Grant Young

- 7 Principles For Perfecting the Princeton Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- How to Replicate A Modern NBA Offense by Grant Young

- Three Great Two-Ball Dribbling Drills For Basketball Development by Grant Young

- Two Rebounding Drills to Win Your Basketball Team Championships by Grant Young

- How to Improve Your Basketball Team’s Defense With the Shell Drill by Grant Young

- How Baylor Basketball’s Scott Drew Develops Elite Guard Play by Grant Young

- Off-Ball Movement Tips and Strategies: Lessons From the NBA Finals by James Locke

- Player Development: Scott Drew’s Tips for Producing NBA Guards by James Locke

- How to Execute a Spread Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- Four Quality Quotes From Four Final Four Coaches by Grant Young

- A Guide to the Pack Line Defense by Alex Martinez

- 3 Defensive Build Up Drills to Improve Team Basketball Defense by Grant Young

- Battle of Two Great Coaches: Best Plays from the NBA Finals Contenders by Justin Tran

- 10 Creative Ways Athletic Programs Can Use a Video Board to Raise Money by Coach Williams

- How to Use 3 on 3 to Improve Your Basketball Team by Grant Young

- How to Defend the Pick and Roll by Grant Young

- Mastering Basketball Defense: Techniques, Drills, and Strategies for Success by Justin Tran

- Three Tips From The Coach Who Developed Giannis Antetokoumnpo by Grant Young

- 2023 NBA Draft: Skills and Technique from Top Prospects by Justin Tran

- From College to the Pros: Transitioning the Dribble Drive Offense by Justin Tran

- Positionless Basketball: Redefining Roles on the Court by Justin Tran

- Revolutionize Your Offense: Proven Concepts to Elevate Your Basketball Game by Justin Tran

- 5 Essential Fastbreak Drills Every Basketball Coach Should Know by James Locke

- How to Run a Circle Offense in Basketball by Grant Young

- Game-Changing Strategies: ATO Plays in the EuroLeague and Olympics by Justin Tran

- How to Stand Out at Basketball Tryouts by Grant Young

- How to Improve Your Basketball Team’s Transition Defense by Grant Young

- Indiana Fever GM Lin Dunn’s Two Keys For Women’s Basketball Coaches by Grant Young

- Strength Training Strategies Every Basketball Player Should Have by Grant Young

- A WNBA Basketball Coach’s Four Priorities In Transition Defense by Grant Young

- Three Adjustments to Make When Your Basketball Offense Isn’t Working by Grant Young

- Three Pillars to Applying Defensive Pressure on the Basketball Court by Grant Young

Four of Olympic Gold Medalist Coach Mechelle Freeman’s Relay Race Strategies

- By Grant Young

Mechelle Lewis Freeman has emerged as a transformative figure in the world of track and field, particularly in the realm of relay racing. Her journey from Olympic athlete to world-class coach demonstrates remarkable leadership and a profound understanding of team dynamics and athletic potential, especially regarding relay race coaching strategies.

As the head coach of the USA Women's Track and Field Relay teams, Freeman has revolutionized how relay athletes train, compete, and conceptualize teamwork. Her own Olympic experience in the 4x100-meter relay during the 2008 Beijing Games provides her with expert insights into the intricacies of relay racing strategy and team chemistry.

Freeman's coaching philosophy extends far beyond technical skills. She emphasizes mental preparation, communication, and collective confidence. Under her guidance, the U.S. women's relay teams have consistently achieved exceptional results, including two Olympic gold medals at the 2024 Paris Games. Her ability to build cohesive teams that perform under intense pressure has set her apart in the coaching world.

What distinguishes Freeman is her holistic approach to athlete development. She doesn't just focus on individual speed but cultivates a team culture where each athlete understands their critical role in the relay's success.

Freeman's strategic coaching and ability to optimize team potential have made her a respected figure in track and field circles. She has conducted several online clinics that share some of the best strategies for success in the 4x100 and 4x400 relay races. We have pulled some of her most pertinent tips and shared them with you below.

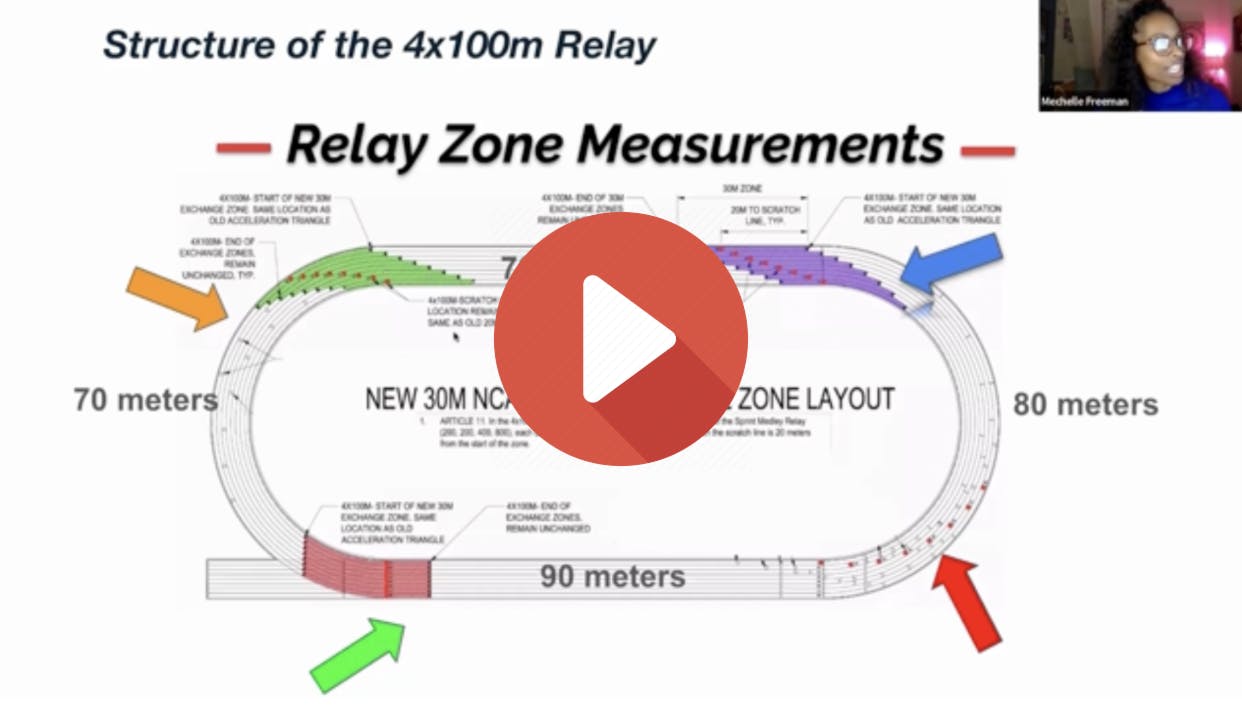

Structure of the 4x100 Relay

In her ‘Mechelle Freeman - Championship Relay Strategies’ clinic, Coach Freeman breaks down the different components of the 4x100 relay into distinct segments based on length.

She explains that the first portion of coming out of the blocks, where the runner needs to focus on creating and sustaining max velocity as quickly as possible around the first time, making for an 80-meter run in total before they’re hitting the second zone.

Then there’s a 30-meter zone behind that ends with the second leg, which starts on the back stretch. The runner will then have a straightaway running opportunity for 130 meters, all the way to the end of the next zone. Therefore, this part of the race (which is considerably longer than the first 80 meters) must be run by someone with straightaway speed.

The third leg requires another crucial turn, which is about 70 meters, and is therefore the shortest leg. This ends with the fourth and final leg, which Coach Freeman calculates at 120 meters, and of course requires the anchor.

The vital aspect here is understanding that, according to Coach Freeman, each leg of a 4x100 relay isn’t exactly 100 meters, and these varied lengths should influence which runners are placed where.

Baton Speed in Exchange Zone

Since there are two different acceleration points in relays, it’s a coach’s job to make sure runners are minimizing differences in individual velocities as much as possible so that baton exchange can take place.

For example, if the exchange occurs at around 85 meters (while the first runner is still near top speed and the second runner has barely gotten going), the exchange is going to have a much more likely chance of error. Not to mention that the second runner only being at about 30% of their max velocity at this point could be slow enough to lose the entire race.

In contrast, if the baton exchange is made right at or right before 100 meters, the first runner will be at around 95% of their max velocity while the second runner has had time to accelerate up to about 85%, which ensures a smoother and faster exchange.

3 Main Components to Succeed

In her ‘Expert Strategies for Speed and Precision during Relays - Mechelle Freeman’ clinic, Coach Freeman conveys three main components to succeed in the passing portion of a relay race:

1. The reading of the takeoff marks

Runners typically leave much earlier than they should because they’re not familiar with where on the track they should be. Therefore, a coach needs to get every runner reading marks the same way.

2. Exceptional and consistent acceleration from both incoming and outcoming runners

Athletes who do not understand the basic concept of acceleration (along with when to accelerate) will be at a distinct disadvantage.

3. Sound passing mechanics

Regardless of how talented your runners are, any relay race can crumble if there aren’t sound and consistent passing mechanics with each and every exchange. The only way to get this right is through constant repetition from the drill side and by coaching the mechanics and timing involved the right way.

Executing the Pass

Speaking of passing mechanics, Coach Freeman conveys that runners must understand they have about two meters to work with on a push pass.

In addition, athletes must be crystal clear on when to say “stick,” and what response that requires from the runner who’s receiving the baton.

What’s more, Coach Freeman says the exchange should occur at shoulder height so the receiving runner is flexible. They should also be leading with the elbow, going joint to joint (shoulder joint to the elbow joint to the wrist joint) in their movement.